I applaud LJ for taking on the New LJ Index project. Coming from a library that has often ranked quite high in the HAPLR Index you would think that I would be quite satisfied with a continuation of this index as a mechanism for peer comparison. However, I have always seen this input-dominant index as flawed. Even when the Dayton Metro Library ranked as high as 6th in its population group, I resisted the urge to breast beat.

The LJ article asks for what changes and new outcome measures are needed. The first step I would suggest is that existing measures be better defined or better methodologies be developed and mandated for collecting and reporting data. Two measures in particular come to mind: circulation (as separate from renews) and patron assistance counts. These are two bread and butter measures of output used by libraries, but my scanning the PLDS rankings on these measures in years past and speaking with library directors and staff at some of the top ranked libraries show that different library policies and practices skew the numbers substantially enough to make them ineffective for the task we would all like to assign them.

Recommendation 1: Libraries should only report first time circulation counts.

I can understand how renewal counts could be reported as supplementary information but renewal counts are becoming less significant in measuring library service. All ILS systems now can easily report first time circulation counts separately from renewals. The growing number of people who can renew their materials online has risen dramatically and now this form of renewal outstrips onsite renewals by a large margin. This is significant as online renewals require no staff assistance. My point is that differing policies on renewals have a bigger impact on circulation count than many other factors such as item limits and loan periods and could have a bigger impact than quality of collections and library hours of availability. Counting only first time circulations is a more accurate measure to use in any peer comparison.

Recommendation 2: Give up on distinguishing reference from other service transactions.

Distinctions between reference and directional transactions have always been subjective. Due to the way in which libraries count and report those transactions, they have proven to be an unreliable measure. Most state and national surveys instruct libraries to eliminate directional counts or at least report them separately, leaving the implied “professional reference assistance” as the outcome being reported. This doesn’t happen. There are such blurred lines between the various types of transactions. Is computer assistance in one category or the other? How about assistance in using self serves circulation computers? When does a query about where to find books on a topic stop being directional and starts being readers advisory? Since the qualitative aspects of distinguishing between these various types of transactions leave them unreliable, why don’t we just report all patron contacts?

Why do I suggest these two changes as a start? Recent experience at the Dayton Metro Library illustrates challenges LJ will face in coming up with a better way to measure library outputs.

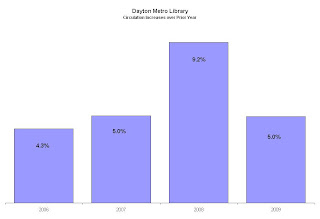

The easiest way to increase circulation is to increase your renewal limits.During the past year the Dayton Metro Library implemented a number of policy changes under an umbrella program labeled the “Urban Initiative”. In 2006 we had a record year of overall circulation but at the same time we saw circulation at most of our urban branches drop. An ad hoc task force brainstormed those causes and triaged them into those that we could impact and those we could not (e.g. the trend of declining urban populations). Twenty-one recommendations were approved by our Board of Trustees and during the past 18 months we have implemented most of those recommendations. Among the changes: reduced fine rates for videos from $1.00 per day to 10¢ per day; elimination of overdue fines for children’s materials; an amnesty on existing overdue fines; purchase of more urban literature; more spending on promotions; and more aggressive outreach to urban schools.

I have been pleased to see substantial successes. Circulation has risen by double digits system wide with a 14.9% YTD increase over 2007 as of May. Better yet urban branch library circulation has also risen by 19.1%. Pretty impressive for a declining population base!

However, I noticed that the systematic door counts didn’t mimic these increases. In recent years we installed electronic door counters in order to systematically and accurately measure this outcome. With those counters in place we have been able to document only a small increase in visitors. What would explain the differing trend lines?

Obviously we must be seeing a large number of items circulated per visit. Or are we? I looked at our circulation statistics another way and was surprised that a substantial percent of the increase in circulation was due to patrons exploiting another change that came about as a part of our urban initiative. One of the more subtle changes was to raise the number of times a patron can renew an item. If an item is not needed to fill a reserve a patron can now renew it up to five times. The previous maximum was two renewals.

Not only were we seeing a dramatic increase in renewals overall, we were seeing a substantially greater increase in renewals performed online. Looking back at recent months I found that when renewals are removed first-time borrowing increased system-wide only by 10.3%. That number is still impressive and more closely coincides with the more modest increases in door counts. However, our big jumps in renewals included a whopping 68% increase in online renewals. Online renewals explained most of the rest of the jump in our circulation. I only see online renewals increasing both as users become more connected and as libraries adopt fewer restrictions. First time circulation as the measure of output is a step toward a better measure.

Counting only reference transactions is like counting only those with right answers!My recommendation about counting and reporting of reference transactions is driven by the inherently subjective and inaccurate methodologies used to create these counts. We recently changed our internal reporting practices in order to improve the usefulness of the data. However we found that the subjective nature of the categories and the sampling procedures we employed did not solve the inherent unreliability of the counts.

The Dayton Metro Library recently began counting our patron assistance transactions differently, using more categories that better illustrate the kinds of staff skills assistance needed by our patrons. These categories distinguish between assistance in using equipment such as computers and copies separately from questions and help with library services such as how to book a meeting room.

After a few cycles of collecting this data, we saw that the grand total of all kinds of assistance was consistent with what we have reported using the old categories. This spring we had a 5% increase in patron assistance transactions (including traditional reference and directional questions). That corresponded with the 10.0% increase in first time circulation we have experienced during the past year.

Unfortunately we also saw unexplainable differences by location. We had branches that were increasing their circulation dramatically but their patron assistance counts were down by as much as 50%. Other locations reported more than a 60% increase in assistance transactions but only a slight increase in circulation. None of these can be seen as consistent with other output measures for these locations such as door counts. Looking back over prior years, we saw these same inconsistencies. It leaves me with little faith in these numbers. Even the distribution of the six types of transactions within a particular location defies explanation. It convinces me that our staff is having troubles consistently counting these transactions. Imagine how inconsistent the counts are between libraries?

I don’t admit this lack of faith in our numbers as a criticism my public service staff. They have been asked to measure a complex task with a flawed measuring stick. We not only have a very subjective way of categorizing our transactions, we reinforce those inaccuracies by the methodology we use to sample and project this outcome.

We count our patron assistance activities during two weeks per year, one in the fall and the second in the spring. I suspect that most other libraries do something similar. Some of the inconsistent results may be due to the differences in school schedules, weather, and other external factors. But you have to suspect that staff moods, management promotion, and other internal factors have a bigger impact. I also suspect that this flawed sampling strategy is adopted by libraries because it is too burdensome to do throughout the year and because they also have so little faith in the numbers. It isn’t worth the bother.

Don’t mistake my comments as a lack of appreciation of the work of our public service staff in aiding our users. We recently asked in a survey what our patrons think of our facilities. Over half of the free text comments we received weren’t about the buildings; users took the opportunity to tell us they just loved our helpful, courteous and knowledgeable staff. These staff members deserve a better means of measuring this aspect of their work. Until that better mechanism is devised and until it is used consistently across the country, we should at least minimize the subjectivity and inaccuracy we introduce with arbitrary divisions between reference and directional and only report the total number of contacts we have with our patrons. It is a start.

I’ve focused on two of the most predominately used counts of library outputs. Both are flawed and can be improved. Certainly more discipline in defining all of our outcome measures is needed. We also need to reject flawed sampling strategies if we are to establish reliable output measures.